Early Maps and Print

Historical map-making began with information gathering—from written reports and surveys, to explorers’ first hand experiences, and sometimes from sources unique to the particular context. The mapmaker would take this information and select elements to include before the map design was transferred to a block or plate for printing.

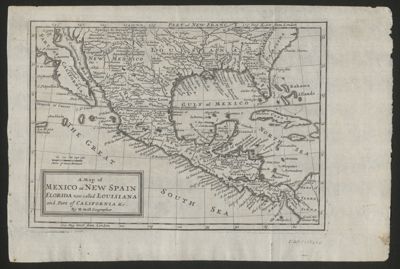

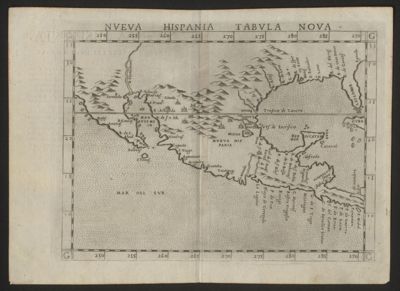

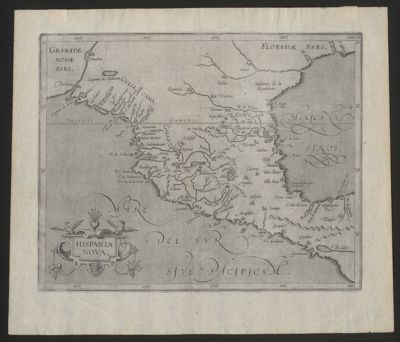

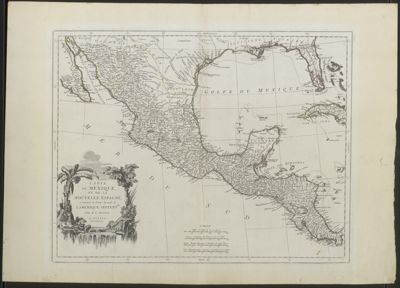

Europeans charted the coastline of the Americas quickly, but the interior was another matter. With the difficult terrain, resistance from indigenous groups, disease, and technical deficiencies (especially the calculation of longitude), it took centuries for the interior of the Americas to be accurately mapped. The Spanish were notoriously secretive about geography, so other European geographers and cartographers during the 16th- through 18th Centuries had to extrapolate and build additions from partial maps and glimmers of information.

The invention of the printing press in 1450 gave rise to numerous books with printed engravings, including maps. Antique maps were generally printed by one of three methods: woodblock (using sections of hardwood joined together), copperplate engraving, or lithography. In the papermaking process, sizing—usually gelatin—was used to reduce the paper’s tendency to absorb water. This reduced bleeding when water-soluble ink or dyes were added to the map, allowing for elaborate hand-coloring.

Woodblock

In producing a woodblock-printed map, the image is carved parallel to the wood grain; it is carved in reverse so that it will appear correct when printed. This method tends to have a stiff, angular appearance and prevents fine detail and shading. The printing process is straightforward: ink is applied to the block and dampened paper pressed to it; however, the blocks are damage-prone and difficult to alter. Modifying a wood block would involve carving a new section, removing the existing section, and inserting the replacement while assuring that new piece fit properly.

Copperplate

By 1600, the woodblock method had been largely displaced by copperplate engraving. Copper, being a soft material, easily permitted designs to be cut into the plates and allowed for considerable detail: flexible lines, curves, areas of tone. Revising a copperplate was a matter of identifying the area that needed modification and tapping out that area of the plate from behind, a definite advantage over woodblocks. To print, the copperplate is heated so that the applied ink would flow into the grooves; slightly dampened paper (to better absorb the ink) placed on the plate; then the plate and paper together passed through a rolling press. The squeezing of the paper into the plate’s lines left characteristic marks on the paper: the lettering and lines were raised; outside of the manual one usually sees a ridge called a plate mark. Lettering required a separate print run on a different press. Copperplate printing was the primary map printing method until the mid-19th Century, when lithography became widespread.

Lithography

Invented in Germany in 1796, lithography is a print process using a flat surface. A mirror of the map design is drawn onto a piece of smoothed limestone, using tusche, a greasy ink. The stone is etched with a weak acid solution and washed with water, then a greasy printing ink is rolled on. The greasy ink is attracted to the tusche and repelled by the damp stone, and the image is transferred to paper. Lithography ushered in improvements including use of metal plates and rollers to produce maps in large quantities, as well as printing larger areas in color.

![[Plan del presidio de San Sabá al de los Adaes y San Antonio de Véxar, comenzando desde el Nuevo Reino de Orleans demarcando todos los presidios, misiones, fuentes, pueblos y demás casas, de que se compone el ámbito de dicho mapa.]](https://api.library.tamu.edu/iiif/2/a4f1991d-9e3c-3dbf-ad67-330884620598/full/!400,400/0/default.jpg)