Immigration and Land Grants

Spanish explorers who documented indigenous nations in northeastern New Spain in their diaries, reports, and histories include Cabeza de Vaca (1527-36), Chapa and de León (1689, 1690), Ramón (1716), Aguayo (1721-22), Rivera (1727), and Rubí (1767). Spanish writings indicate that while numerous and diverse, these nations were interconnected through extensive trade networks and periodic aggressive engagements. Although the names of approximately 140 indigenous nations are given across eleven well-known diaries of Spanish explorers, the total number of tribes may never be known. Among those named are the Bidai, Karankawa, Tonkawa, Caddo, Tawakoni, Apache, Comanche, Jumano, Osage, Kiowa, Coahuiltecan, and Wichita.

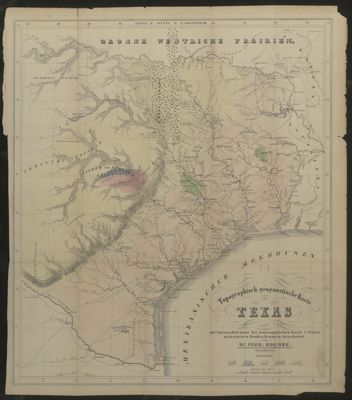

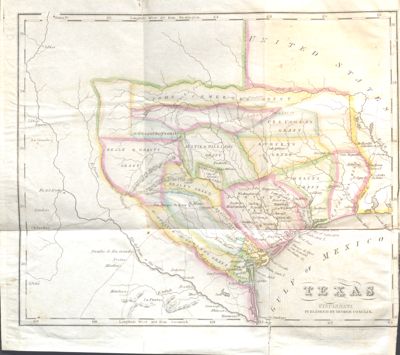

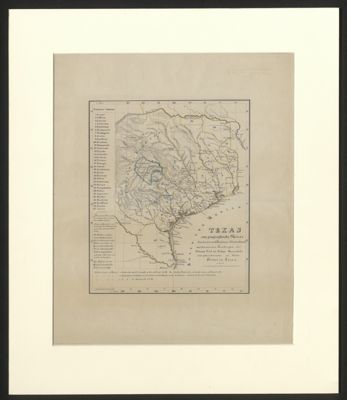

Some maps label specific geographic areas with indigenous group names, but historians know that the tribal situation during Spanish exploration in Texas was complicated by migration activity. Peoples seeking to maintain themselves and their practices moved into and out of areas of Texas because of Spanish and Apache, then Comanche pressure, principally from the southwest and north. After the withdrawal of the French in the 1760s, colonial policy in northeastern New Spain was influenced by the increasing resistance of indigenous groups, particularly the nomadic, well-armed horsemen from the Great Plains. The Spanish response was to use Texas as a buffer zone to defend New Spain.

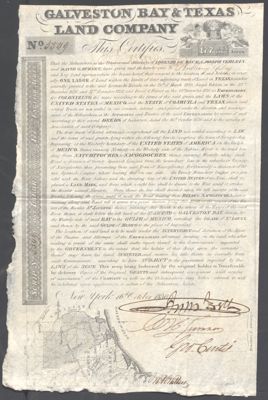

The Empresario System

In 1819, Spain adopted the empresario plan. The Texan frontier saw sporadic French and Spanish settlements, but Spain tightly regulated access to its colonial possessions, and in response to the threats to the north from Apachería and later Comanchería, and European outposts in the Mississippi Valley, had considered ways to make Texas into a buffer state for New Spain. Spain also wanted to attract foreign settlers like the Irish and Germans. With the empresario plan, a modification to existing colonization law, more than a dozen empresarios agreed to colonize Texas under specific conditions. This method was continued by Mexico.

Mexico’s 1824 colonization law regulated the empresario plan for Texas until it was superseded by the Law of April 6, 1830, designed to constrain the empresario system. The law aimed specifically to reduce immigration from the United States, but since the law could be violated with impunity, immigration into Texas was perhaps diminished, but did not stop. The empresario system continued under the Republic, but with some changes. While the Mexican empresario system had held slavery in check, restrictions were removed with Texan independence, resulting in an expansion of the plantation system. The 1820s saw the immigration into Texas of Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, Shawnee, Delaware, and others pushed west by the actions of the federal government. In the 1840s, the Adelsverein Society promoted mass German emigration, often by indenture; their first settlement was near Comal Springs under the leadership of Prince Carl of Solms-Braunfels. The late 19th Century saw Czech, Italian, and other European immigration.

In the United States in the 19th Century, eyes were on Texas. Bank failures, land speculation, and depletion of soil fertility rendered many of those who settled east of the Mississippi “land poor.” When Texas moved to being a state in Mexico, the changing political climate and much-publicized inexpensive land had encouraged flow of settlers from the United States. Numerous guides with maps were produced from the early 1830s onward to promote land availability, to show mineral wealth, and to encourage settlement.